Higher blood pressure is clearly associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular events, but can hypertension independently promote cognitive dysfunction as well? This question was reviewed by Costantino Iadecola, MD, Director of the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute, Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University, New York, New York, and colleagues in a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Their findings were published in the December 2016 issue of Hypertension.

Researchers found good evidence that hypertension can damage cerebral blood vessels and promote ischemia in white matter.

There was a strong association between the presence of hypertension during middle age and cognitive dysfunction later in life; however, the relationship between hypertension among older adults and cognitive dysfunction was less clear.

Treatment of hypertension was associated with favorable changes in neuroanatomy and pathology, but it remained unclear whether antihypertensive therapy directly improves cognitive function during old age.

Could elevated blood pressure result in changes in brain volumes, even among younger adults? The current study by Schaare and colleagues addresses this question.

Study Synopsis and Perspective

Elevated blood pressure in younger adults appears to be tied to an increased risk for dementia in later life, new research showed.

Results of the rare study conducted in individuals age 40 years or younger showed individuals with blood pressure levels >120/80 mm Hg but who were not necessarily considered hypertensive, defined as ≥140/90 mm Hg, had lower brain volumes in regions associated with cognitive impairment.

The findings supported a potential neuroprotective benefit of regular blood pressure screening in 19- to 40-year-olds to identify individuals at risk.

"Our research provides new insights about the relationship between blood pressure levels and the brain. The study shows that blood pressure above 120/80 mm Hg is linked to reduced gray matter volumes [(GMVs)], which emphasizes the importance of blood pressure variations in so-called 'normal' ranges for young adults' brain integrity," lead author Lina Schaare, PhD candidate, department of neurology, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, told Medscape Medical News.

"This suggests that modestly elevated blood pressure levels should be targeted already in early adulthood to preserve brain health throughout life," Ms Schaare added.

The study was published online January 23, 2019 in Neurology.

Young Population

Prior studies support an association between hypertension in midlife and risk for late-life cognitive dysfunction, including late-onset Alzheimer disease.

Other researchers took this a step further and looked at specific brain structures. In multiple studies, associations emerged between hypertension and subclinical functional and structural brain changes, including brain volume reductions in the medial temporal lobe and other regions.

Neuropathologic studies have also linked elevated blood pressure in midlife with lower postmortem brain weight and increases in hippocampal neurofibrillary tangles and hippocampal and cortical neuritic plaques.

"However, effects of elevated blood pressure on adult brains before the age of 40 are unclear," the researchers noted.

To test the hypothesis that elevated blood pressure would correlate with lower regional brain volumes, particularly in the frontal and medial temporal lobes, Ms Schaare; principal investigator Arno Villringer, MD; and colleagues assessed 4 unpublished datasets of individuals not previously diagnosed with hypertension.

Investigators identified 423 participants ages 19 to 40 years from larger studies conducted in Leipzig, Germany between 2010 and 2015. They combined the data using image-based meta-analysis.

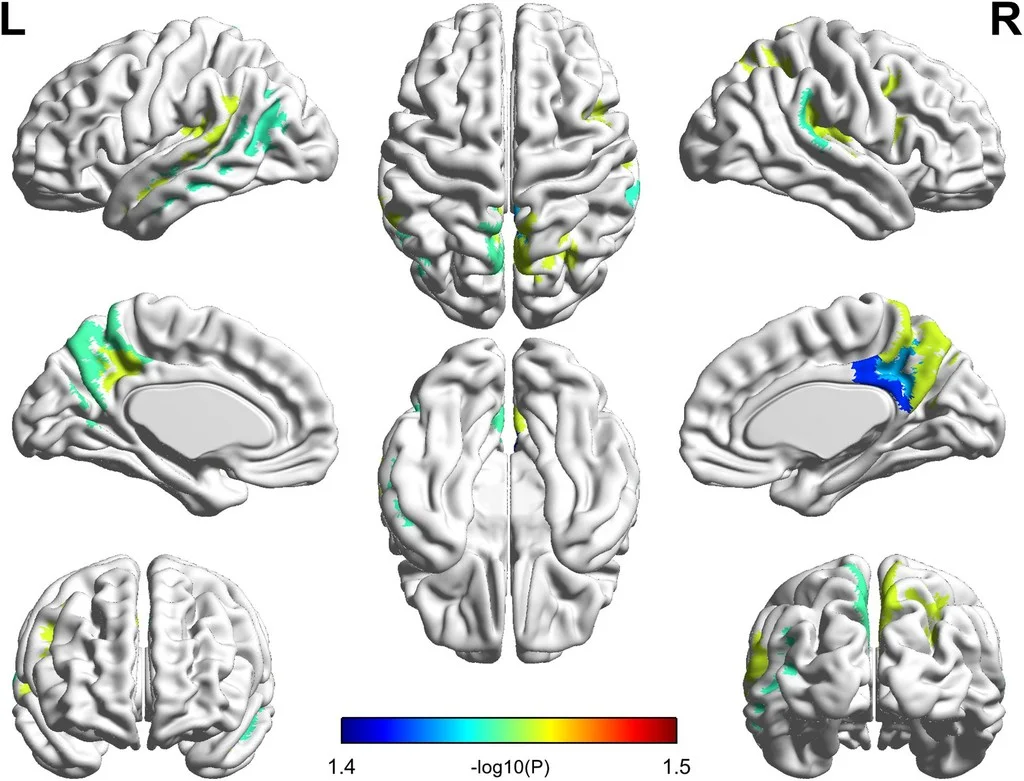

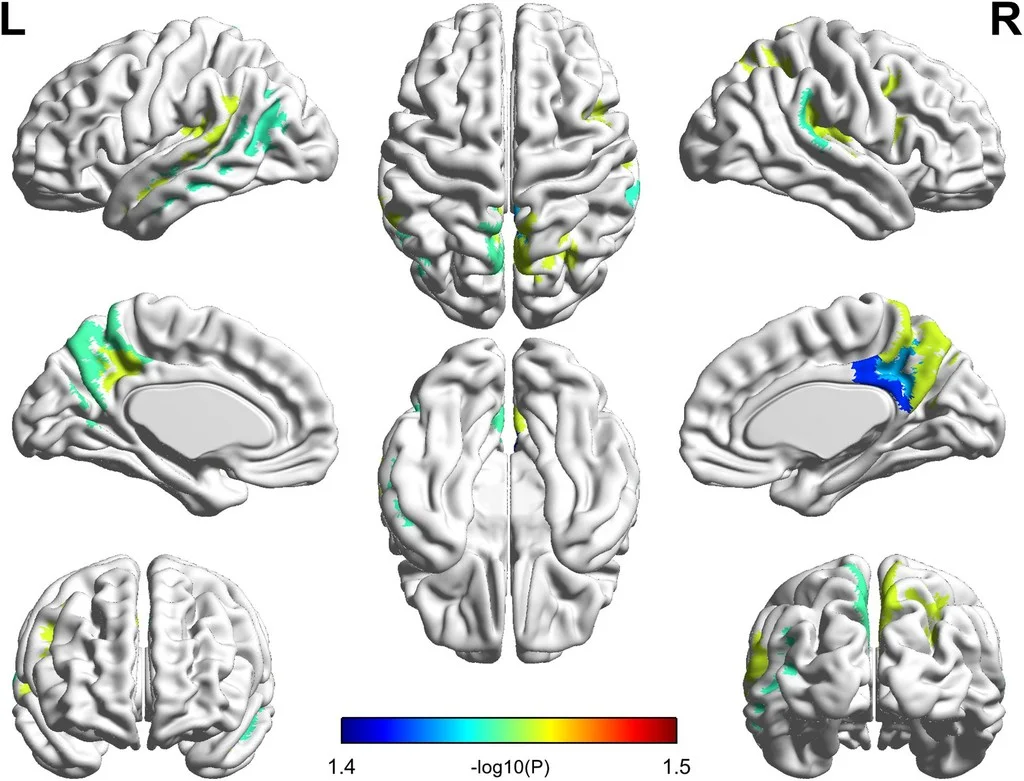

A statistical mapping technique called voxel-based morphometry was used to detect small differences between region volumes on T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scanning.

The mean age of the cohort was 27.66±5.27 years, and 42% of participants were women. Investigators measured systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) at varying times of day. They then averaged these multiple measurements to one average SBP and one average DBP reading for each participant.

Results Speak Volumes

Participants were classified according to blood pressure levels using 2013 European guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. In this system, individuals in category 1 had SBP <120 mm Hg and DBP <80 mm Hg; category 2 had SBP 120-129 mm Hg or DBP 80-84 mm Hg; category 3 had SBP 130-139 mm Hg or DBP 85-89 mm Hg; and category 4 had SBP ≥140 mm Hg or DBP ≥90 mm Hg.

In addition to comparing brain region sizes by blood pressure category, Ms Schaare and colleagues also assessed total brain volumes.

Higher SBP was linked to lower GMV in the right paracentral/cingulate areas, bilateral inferior frontal gyrus, bilateral sensorimotor cortex, bilateral superior temporal gyrus, bilateral cuneus cortex, and the right thalamus.

Increases in DBP were associated with lower GMV in the bilateral anterior insula, frontal regions, right midcingulate cortex, bilateral inferior parietal areas, and right superior temporal gyrus."As expected, increases in [SBP] and [DBP] were associated with lower GMV," the researchers noted.

When the investigators conducted a subanalysis that compared the category 4 to category 1 groups, they again found higher blood pressure was associated with lower GMV in multiple brain regions. Another comparison between sub-hypertensive participants (categories 3 and 2 combined) vs category 1 yielded similar findings.The researchers did not uncover any significant associations between elevated blood pressure and total brain size.

A Shift to Earlier, Subtler Signs?

"Our results show that blood pressure-associated gray matter alterations emerge earlier in adulthood than previously assumed and continuously across the range of blood pressure," the researchers noted.

"Previously, brain damage related to high blood pressure has been assumed to result over years of evident blood pressure elevation," Ms Schaare said, "[b]ut our study suggests that subtle decreases in the brain's [GMV] can be seen in young adults between 20 and 40 years of age who have never been diagnosed with hypertension and who have blood pressure only slightly above 120/80 mm Hg."

The study also "highlights the importance of taking blood pressure levels as a continuous measure into consideration, which could help initiate such early preventive measures," the researchers noted.One caveat is the study points to an association, not causality, between lower brain volumes and hypertension. Although the exact mechanism behind the association remains unknown, the researchers noted, "it has been proposed that medial temporal and frontal regions might be especially sensitive to effects of pulsation, hypoperfusion, and ischemia, which often result from increasing pressure."In terms of next steps, Ms Schaare said, "More research, especially longitudinal studies, is needed to investigate whether such alterations in young age could increase the risk for stroke, dementia, and other diseases later in life."

Future research could also look at any differences by sex, they noted."The topic of sex differences in brain structure related to blood pressure is an interesting open question for future investigations," stated the researchers.Interestingly, a study previously reported by Medscape Medical News pointed to a higher risk of developing dementia among women with hypertension in their 40s compared with men.

Further Investigation Warranted

Commenting on the findings for Medscape Medical News, Anna DePold Hohler, MD, fellow of the American Academy of Neurology; chair, department of neurology at St. Elizabeth's Medical Center; and associate professor of neurology at Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, described the study as a "novel analysis."Nonetheless, she cautioned it does not prove causality.

"The study appears to imply that blood pressure causes brain atrophy, but it is possible that instead those with brain atrophy have more autonomic dysregulation, and therefore hypertension. This study provides a possible correlation between blood pressure and brain volume that should be further explored," she said.

Schaare and DePold Hohler have reported no relevant financial relationships. The study was supported by the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences.

Study Highlights

- Study patients were collected from 4 different research protocols all completed in Germany. The current study evaluates adults between 19 and 40 years of age who had blood pressure measurement and brain magnetic resonance imaging study performed between 2010 and 2015.

- All study participants had no history of hypertension or other significant chronic illness. Adults taking anti-hypertensive medications were excluded from study analysis.

- The main study outcome was the association between blood pressure and GMV. Researchers also assessed whether blood pressure was related to other brain volumes.

- 423 adults provided data for study analysis. The mean age of participants was 27.66±5.27 years, and 42% were female. The mean SBP and DBP values were 123.2±12.19 and 73.38±8.49 mm Hg, respectively.

- Higher SBP and DBP was associated with lower GMVs. Comparing blood pressure values ≥140/90 mm Hg with those <120/80 mm Hg, GMVs were lower in the frontal, cerebellar, parietal, occipital, and cingulate regions.

- The hippocampus was particularly affected by higher levels of both SBP and DBP.

- Even modestly high SBP values 120-129 mm Hg and DBP values 80-84 mm Hg were associated with lower GMVs.

- Blood pressure did not significantly correlate with total brain volume.

Study Highlights

- A previous review by Iadecola and colleagues found a strong association between the presence of hypertension during middle age and cognitive dysfunction later in life; however, the relationship between hypertension among older adults and cognitive dysfunction was less clear. Treatment of hypertension was associated with favorable changes in neuroanatomy and pathology, but it remained unclear whether anti-hypertensive therapy directly improved cognitive function during old age.

- The current study by Schaare and colleagues finds that even minimally elevated blood pressure values during early adulthood are associated with a loss of GMV, particularly in the hippocampus. Total brain volume did not significantly correlate with blood pressure in young adults.

- Implications for the Healthcare Team: The healthcare team should be aware of the potential negative effects of elevated blood pressure among young adults and promote blood pressure screening and lifestyle interventions to maintain lower blood pressure values.

* the title figure shows a decrease in the volume of the left superior temporal sulcus, right posterior cingulate gyrus and transverse temporal sulcus, precuneus and subparietal sulcus compared to healthy patients.